“Algorithm” has become one of our era’s prominent buzzwords, with hardly any political or economic debate lacking some reference. Media coverage of algorithms is also growing dramatically – today, the topic can even be found on newspapers’ front pages. However – or perhaps because of this – it is worth taking a look beneath the surface of the debate and asking whether citizens are really aware of where algorithms are being used, and how algorithmic systems function. In May 2018, we published the results of a representative survey in which Germans were asked about their knowledge and attitudes regarding the topic of algorithms. The data we collected showed the following: In Germany, there is a widespread lack of knowledge on the issue of algorithms, a great deal of incertitude regarding their opportunities and risks, and significant discomfort regarding judgments and decisions made by algorithms. The survey indicated that a broad public debate regarding the opportunities and risks associated with algorithmic decision-making had yet to commence.

We have taken the results of the Germany-wide survey and current political developments regarding algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) as an opportunity to expand our view to the European level. Ultimately, the increasing influence of algorithmic systems will respect no national borders; rather, it is a global development. The European Union (EU) itself is trying to position itself as a counterweight to pioneers such as the United States and China with regard to the social embedding of algorithms and AI. Yet what do Europeans, in fact, know about algorithms? Which areas of deployment are Europeans familiar with, and what associations do they hold with such use? Does Europe’s population see algorithmic decision-making more as an advantage or a risk?

Knowledge as a foundation: Building competencies for an informed discourse

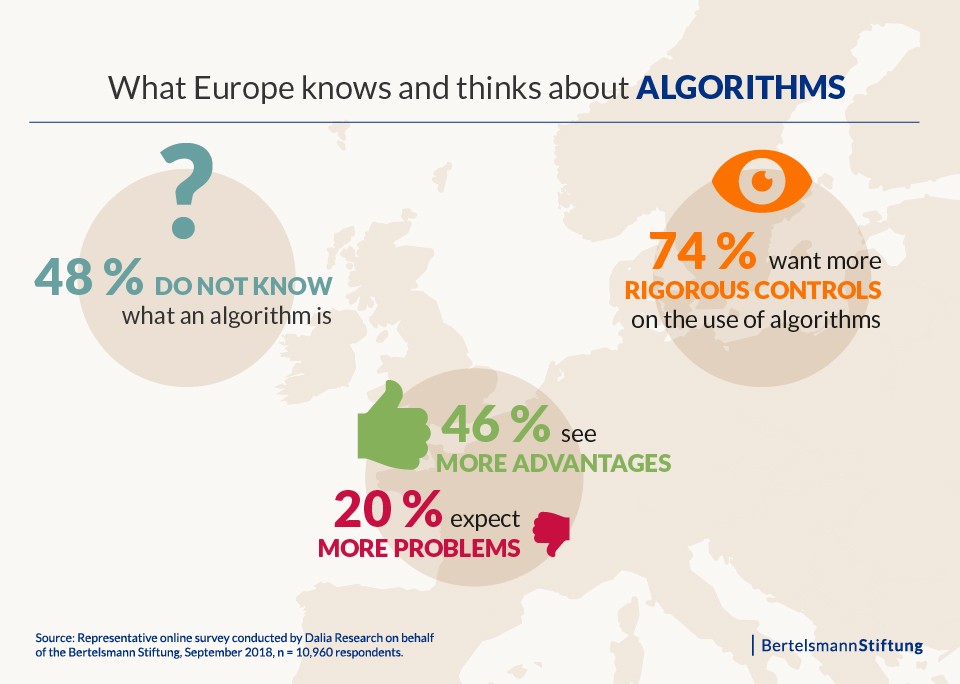

The results of our European-wide representative survey are also sobering: Nearly half of Europe’s population does not know what algorithms are, or that they are already in use in numerous areas of life. The results show that the debate on this issue remains in its early stages across Europe as well, even though algorithms already influence our daily lives. However, it should be noted that despite this lack of knowledge, people in Europe see more benefits than problems associated with the use of algorithms. The share of people holding this opinion climbs with the level of previous knowledge about algorithms. That is, those who know a lot about algorithms bring a more positive fundamental attitude to the topic, without losing sight of the associated risks.

If people know nothing about a subject, they can do no more than blindly trust or intuitively mistrust. Therefore, one goal should be a broad campaign of popular capacity-building; this would enable people to form considered opinions and engage in a factually informed debate. Enlightened citizens today need a basic understanding of the world of algorithms (“algorithmic literacy”) in order to be able to participate autonomously in and help shape public life.

Trust as the key: Establishing effective oversight mechanisms

The present survey makes it clear that Europeans do not necessarily want to see algorithms employed. Despite a fundamental awareness of the potential of such technologies, many associate negative concepts with their use. For example, 34 percent of Europeans see the use of algorithms linked with an increase in power for programmers. For this reason, people want humans to continue playing a central role in areas of use that are relevant to social inclusion. In this regard, a large majority of the population desires that algorithms be subject to stronger control measures.

Ultimately, it is only effective oversight mechanisms of this kind that will allow trust in algorithmic systems to increase, in turn enabling such technologies to fully develop their benefits for society. The most-requested approaches, such as a right to a second opinion, a requirement that algorithmic processes be identified as such, and improvements in the ability to reconstruct algorithmic decisions, offer ideas of how such oversight might be concretely constituted. In this regard, only a broad spectrum of measures can ensure that algorithms will be designed to promote public welfare.

Europe as a focus: Learn from other countries and act together

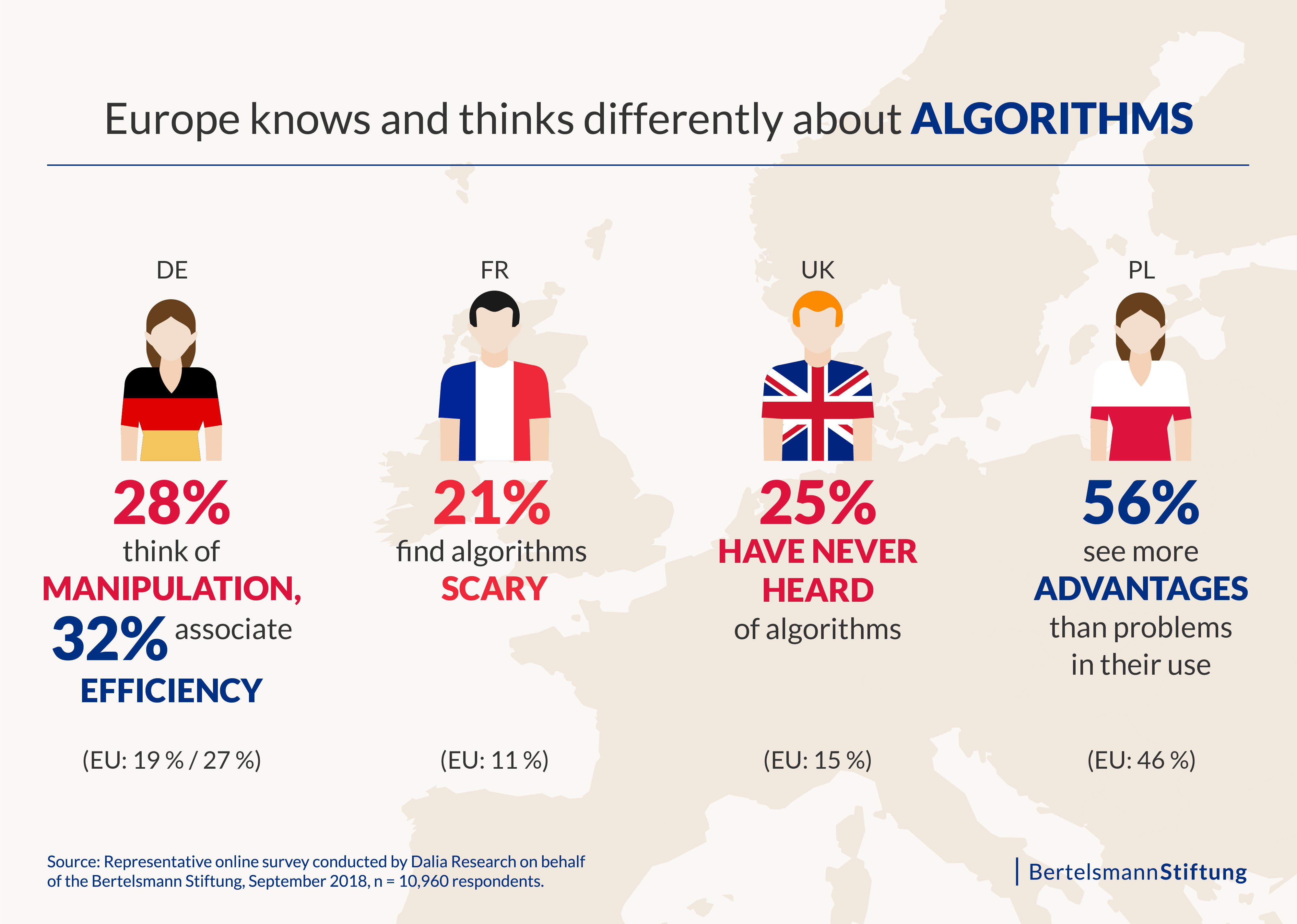

This survey is one of the first to provide a quantitative, primarily cross-European assessment of attitudes regarding algorithms. As such, it underscores how underserved the European perspective on this issue in public debates has been. Since the EU General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) has come into effect, it has become apparent that Europe as a whole – not simply national governments – has the real capacity to shape the digital sphere. At the same time, the comparison between the six most populous EU countries shows that there are quite significant differences with regard to knowledge and opinions about algorithms.

A European perspective should, therefore, be brought into greater focus in two different respects. On the one hand, a look at other countries’ actions is always worthwhile. For example, the Poles stand out with an above-average level of knowledge and a particularly high degree of receptiveness to algorithms, while the debate in Germany appears to be critical, but balanced. EU member states can learn from one another in this regard. On the other hand, the discourse regarding the use of algorithms can and must be considered and conducted across national borders throughout Europe. The European Union should engage as a strong actor seeking to shape the design of algorithms with the public interest in mind, asserting its global influence as it does so. Over the course of time, it will be important not simply to copy the strategies of other major economic powers, but rather to employ the EU’s market and regulatory powers to promote the ethically responsible use of algorithms.

This study was produced in cooperation with our colleagues in the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s eupinions project as well as Dalia Research. Further information regarding the methodology underlying the survey can be found in chapter 1 of the study.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Write a comment